Transparency and Security: A Framework for Information-Sharing Among AI Safety and Security Institutes

Context: The international AISI Network

Last November, the inaugural meeting of the international network of AI Safety Institutes (AISIs) was held in San Francisco. Participating AISIs committed to pursuing research on risks and capabilities of advanced AI systems, building common best practices for testing, and facilitating a consensus on how to interpret these tests; they also agreed to “increase the capacity for a diverse range of actors to participate in the science and practice of AI safety”. If these commitments are upheld and built on, the international AISI network could – in time – become an invaluable forum for AI risk reduction. AISIs recognised that reaching the full potential of the network requires sharing key information. As a first step to this end, they promised to share relevant research findings, results from domestic evaluations, approaches to interpreting tests of advanced systems and technical tools “as appropriate” with each other. While the international landscape has undoubtedly shifted since last November, and the UK AI Safety Institute is now the AI Security Institute, information sharing remains a necessary ingredient for AI risk reduction, enhancing both resilience and preparedness.

The UK and the US have frontier AI companies in their jurisdictions and AISIs with more capacity, which means that they can access and produce more relevant information than other AISI countries. While both AISIs’ access is not unlimited or infinitely robust, their information sharing policies (or what the UK and the US AISI deem “appropriate” grounds for sharing) could disproportionately influence the information available to other AISIs. This information could impact whether other countries in the AISI network can adapt their policies to current knowledge on frontier models (e.g. evaluation results) rather than basing policies on outdated data. It could improve AISIs ability to push on the frontier of security and safety research, rather than duplicating existing work to catch up. Further, could foster a broader consensus on how to interpret new evidence or test results, and help avoid misunderstandings, overreactions or underreactions. These and other consequences of information sharing can, as this piece lays out, have a number of positive implications for the UK and the US AISI if risks of oversharing are known and addressed.

This piece summarises key findings from my research on the benefits and risks of the UK and US AISIs sharing different kinds of information with the international AISI network and a provisional framework for which categories of information should be considered “appropriate” for sharing from a UK and US AISI perspective. This work was done over the course of the Summer GovAI Fellowship, shared with the US AISI and UK AISI, forthcoming on arXiv.

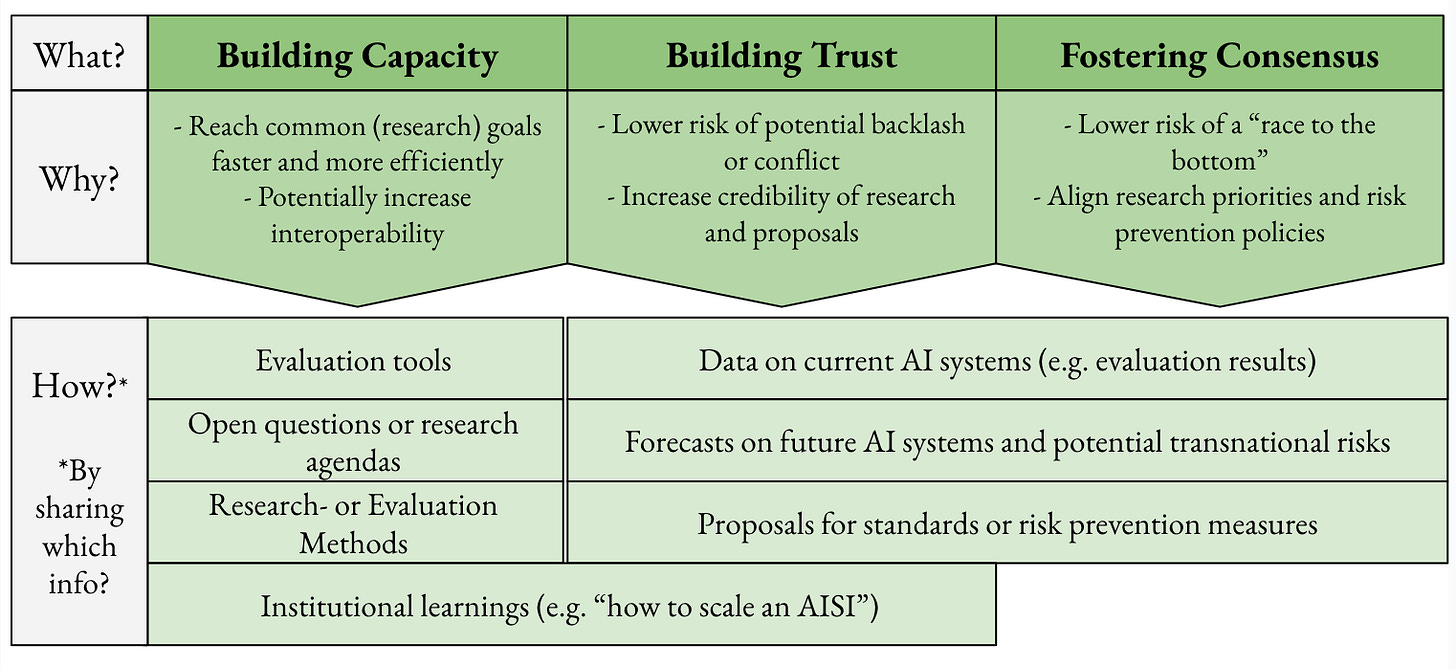

1. How can sharing information with the AISI network benefit the UK AISI and the US AISI?

Fostering consensus

An informed international consensus reduces the risk of overregulation of UK or US based companies. Consensus on how to produce and interpret research results could enhance interoperability between AISIs, increasing the chance that AISIs contribute to common goals effectively. Furthermore, many risks from advanced AI systems have cross-border implications. Because of this, it is in the interest of the international community to avoid a scenario where actors race to lower standards (and riskier activities) to gain a competitive advantage. To lower the probability of such a scenario, AISIs can share their research about which activities and models are risky, standards on how to determine this risk and concrete evidence on particular models. These insights can help more jurisdiction adopt more responsible policies. Building a consensus on the probabilities of specific global security risks could also build an important foundation for increased multilateralism.

Building trust

Transparent sharing of information about an organisation’s own policies and posture towards this increasingly powerful technology can serve as a confidence-building measure and assure others that international interests are taken seriously. It can reduce foreign suspicions of hypocrisy and lend credibility to international proposals and commitments. While this benefit might seem negligible in the short term, countries pushing the frontier of ever-increasing AI capabilities could require significant amounts of trust from the international community in a future where AI capabilities are thought of as coming closer to a “decisive strategic advantage.” Similarly to consensus, this increased trust could build an important preparation for futures where intensified international collaboration is desired by the UK or US AISI.

Building capacity

Sharing information can also help other AISIs build capacity. While there is an altruistic reason to pursue this goal, other reasons should also be considered. If the UK AISI and the US AISI proactively engage in this kind of information sharing, they can not only gain international prestige, but can also increase the speed at which policy-relevant research is completed. If, for example, the UK AISI effectively broadcasts to other AISIs how its institutional structure allows it to be both adaptive and efficient, if it shares their current research frontier and technical tools to conduct evaluations, other AISIs will more likely produce material that is valuable to the UK AISI’s goals.

2. Risks of information sharing: the likelihood of leaks

A wider range of actors having access to information always increases the likelihood of leaks. It's in the interest of the UK AISI and the US AISI to minimise the risk of leaking information which might be sensitive in two ways.

First, AISIs rely on a cooperative relationship with AI companies for the foreseeable future for their own access to information and collaboration on standards building. If AISIs overshare proprietary information (e.g., non-public pre-deployment evaluation results), this may cause AI firms to lose confidence in their national AISI, which could undermine the AISI’s future ability to fulfill their mandate.

Second, some information (like advanced AI capabilities research, model information, or sensitive cybersecurity details) could be misused by bad actors for malicious purposes or help geopolitical adversaries to catch up to the US or the UK. Other information might not be misused, but might still promote capability enhancement in unintended ways, for example if confidential information on a new frontier (like pre-deployment evaluation results) is leaked. Detailed information about the possibility of powerful future or existing AI models could encourage competitors of the UK and the US to invest more resources into catching up or surpassing a British or American state of the art. It could also encourage bad actors to invest in more advanced methods of IP theft.

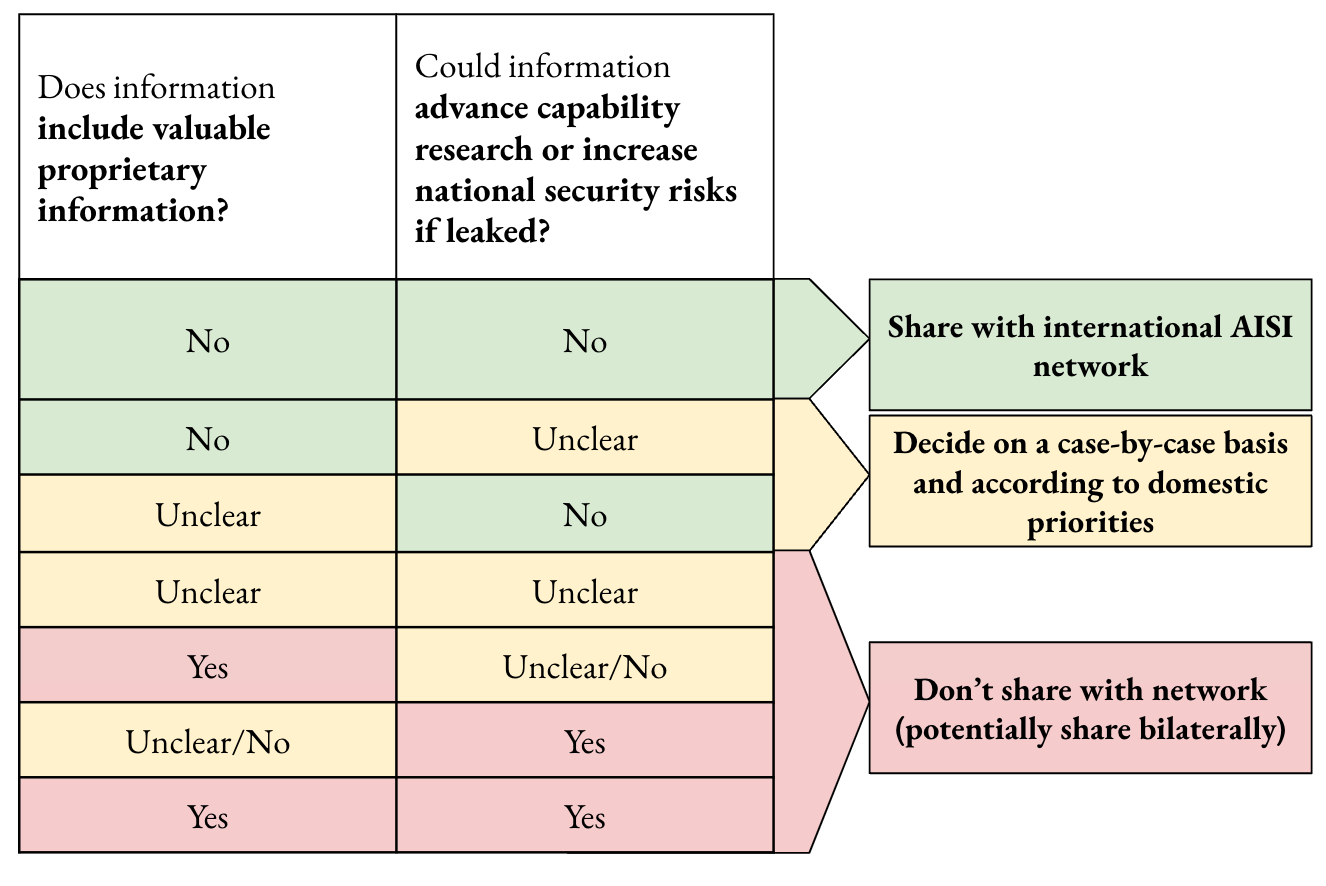

These constraints, however, should not lead anyone to believe that sharing information in general is unreasonable. Some kinds of information are significantly more sensitive than others. Some aren’t sensitive at all, but still have some of the benefits outlined in the first section. Some categories force decision-makers into a trade-off or a sharing decision on a case-by-case basis. The simplified provisional framework in fig. 2) illustrates how decision-makers could distinguish between these three categories.

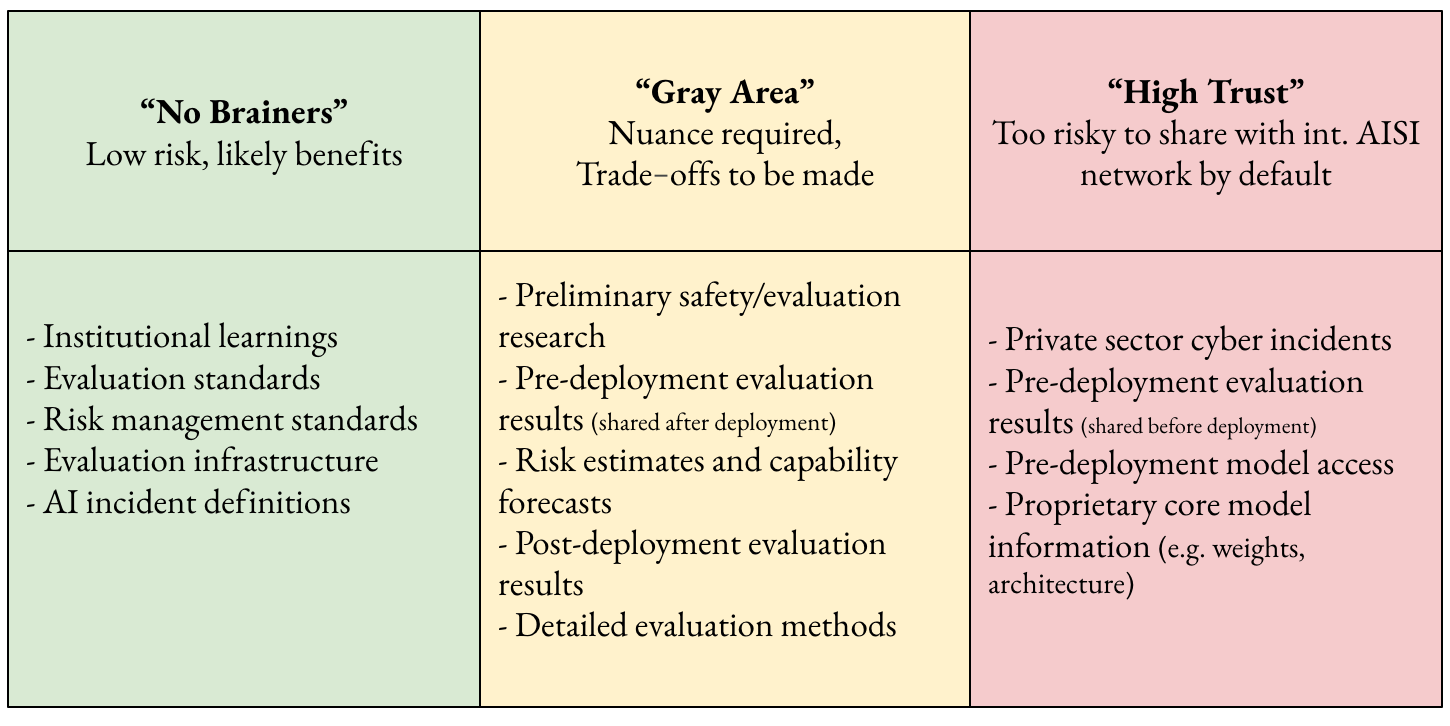

3. Examples of information (not) to share with an international AISI Network

Some information can be shared with the international AISI network with very low risks but almost definite, valuable benefits. An example would be detailed guidance on the institutional design and organisational culture of the UK AISI. Lessons on how to scale up an ambitious organisation and remain adaptable to continued technological progress could improve the speed at which more nascent AISIs could contribute to the network's goals. Another example would be to proactively share information on unresolved or unclear definitions for better mutual understanding (e.g. how to precisely interpret the term “incident” for potential incident reporting standards). This could speed up the consensus-building process and demonstrate an active interest in tracking and preventing risks from AI.

Other categories of information involve trade-offs, or a risk-benefit estimation that requires a more nuanced policy. For example, sharing detailed evaluation methods with the AISI network could help currently under-resourced foreign AISIs to conduct evaluations. However, some evaluation methods can be used for improving a model’s capabilities – and potentially for nefarious misuse if leaked to a broader population. For example, to elicit a model’s ability to design weapons of mass destruction, an AISI might have to create datasets containing information about such weapons. The magnitude of the risks and the benefits of sharing detailed evaluation methods depends on the specific evaluation method – and the specific priorities of the sharer.

Some information presents a large enough risk that sharing it with the entire international AISI network doesn’t seem to be in the interest of the UK or the US AISI. This includes information that would make either misuse or the empowerment of geopolitical adversaries and competitors much more likely if leaked or that includes valuable intellectual property of frontier AI companies (e.g. core model information, pre-deployment evaluation results shared before deployment). While it might still be useful to share some potentially sensitive data, for example intelligence on a cyber incident report at an AI company, with specific trusted partners, the AISI network in its current form seems to be the wrong forum for these cases.

Conclusion

Ideally, policymakers and researchers would have the capacity to examine each piece of information on a case by case basis, have lengthy discussions and conduct extensive research on the specific consequences of sharing a particular piece of information with a specific actor. An overly broad categorisation always leaves value on the table or increases the risk of unintended consequences. But because this ideal nuance requires unrealistic amounts of time, resources and explanations, some generalisations and categories are necessary. This piece (and the research it summarises) hopes to provide some useful, if limited, grounds for more informed decisions.

---

Readers interested in getting a more extensive view or reading about further research questions are welcome to read the forthcoming paper here or reach out to thurnherr.lara@gmail.com.

.png)